A comment on the manifesto for behavioural science

I wrote this post based on notes for a proposed “lunch and learn” session. Illness got in the way, so rather than let those notes sit on the shelf, I’ve cleaned them up to share here. Many points were intended to be (provocative) conversation prompts rather than statements, so a few parts are light on evidence or end with a question.

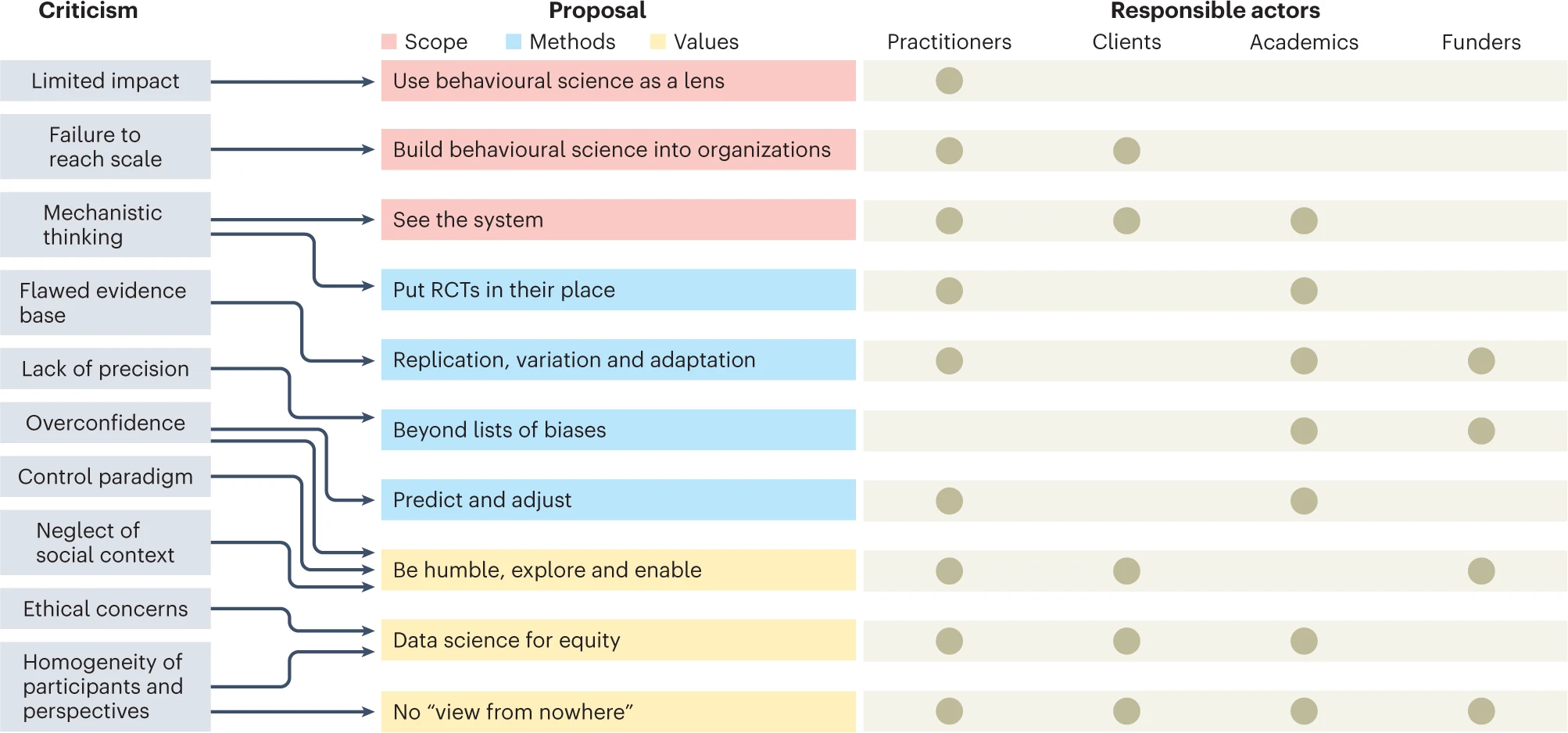

In the first half of 2023, A manifesto for applying behavioural science was published in Nature Human Behaviour. Written by the head of the North American arm of the Behavioural Insights Team, Michael Hallsworth, the manifesto “looks at the challenges facing the field and sets out ten proposals to address them.”

The Behavioural Insights Team also published a longer version of the manifesto, plus a summary document. Hallsworth gave me the opportunity to comment on a draft of the long-form manifesto, so I have a small insight into its development.

Rather than address the document as a whole - I must admit I am sceptical of manifestos for direction from up high - I am going to discuss three of Hallsworth’s proposals:

- See the system

- No view from nowhere

- Data science for equity

See the system

The summary table in the Nature Human Behaviour article describes the “See the system” proposal as follows:

Use aspects of complexity thinking to improve behavioural science so that it can exploit leverage points, model the collective implications of heuristics, alter specific features of systems to create wider changes, and understand the longer-term impact on a system of a collection of policies with varying goals.

Putting this section into my words, much of the public policy territory in which we work is a complex adaptive system. That is, there is a dynamic network of many interacting agents, each with their own strategies. They are constantly acting and reacting and adapting to the environment they find themselves in. Changes are not linear. Small changes can cascade into large consequences. Major efforts can produce little change. “Emergent” behaviour can arise from these interactions, with the system as a whole producing something more than the sum of its parts. If we examine public policy issues with this lens, we might be able to identify leverage points, model the collective implications of people’s decision making strategies, make system-level changes, and understand the impact of multiple policies.

Hallsworth illustrates this proposal with the UK tax on sugared drinks. This tax was implemented in tiers, with drinks with higher sugar content hit with higher taxes. While this might be seen as a way of changing consumer behaviour via higher prices for the sugary drinks, this approach primarily affected sugar consumption in soft drinks by altering the incentives presented to manufacturers. They could reduce the price of their product by reducing the sugar content. Price signals via a tax reduced the sugar content of the drinks on the shelf.

Before digging into the proposal and example, I want to describe two related concepts, chaos and complexity. Both involve the study of non-linear dynamics.

Chaos concerns the study of dynamic systems that are sensitive to the initial starting conditions.

A famous example is Edward Lorenz’s replication of results of his weather simulations. He took the numbers from a previous weather simulation, re-entered them and started the simulation. He found that these new simulations diverged wildly from the previous runs. When he examined the results, he realised he was taking numbers from the prior simulations to six decimal places. Beyond six decimal places, there was variation. These very slight changes in initial conditions led to large divergences over time. This idea is typically referred to as the butterfly effect; a butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon causing a tornado in Florida.

Chaos suggests there is an inherent limit in our ability to predict weather and other chaotic systems. Seemingly insignificant short-term variations from the model will cascade into larger differences.

Chaos can emerge in very simple systems. Lorenz’s weather simulation was based on just 12 equations. Robert May (1976) famously showed that by adjusting a single parameter ‘a’ in a deterministic equation, he was able to generate anything from a stable equilibrium to multiple equilibria to what looks like random noise.

Complexity also relates to non-linear systems, in which order can emerge at a higher level that’s not easily seen as the sum of the lower parts. Complexity theory is the study of these systems. Complex adaptive systems are a type of complex system with agents who learn and adapt in the changing environment, adding an additional complication to the study of the dynamical system.

What does embracing this complexity mean for applied behavioural science?

I see two possibilities.

The first, suggested in the manifesto, is that we can identify leverage points to trigger a large change. Imagine you could control the parameter ‘a’ in May’s equations. The sugar tax is one example, manipulating the price of sugar. Similarly, if trying to regulate carbon emissions, instead of identifying all the different sources and setting specific regulations around them, you could simply set a carbon price.

The second possibility from taking complexity (and chaos) seriously is that some features of the policy environment will be inherently unpredictable.

To discuss this, let’s dig into that example of the sugar tax more deeply. A tax on sugar content of soft drinks led to organisations to reformulate their products (sidestepping the question of whether this is complexity or just second order effects). However, obesity in the UK has continued to go up. The pandemic didn’t help, but it was going up before that. The best we have are desperate data mining studies that, after enough slices and dices, claim a benefit for year 6 girls (but fatter year 6 boys) (Rogers et al., 2023).

So, despite the second order effect of reformulation of soft drinks, for the measure of interest, there was no measurable reduction on obesity. (To be fair, it’s questionable whether you’d expect it to be detectable.) And what of other measures? Over 300 million pounds a year out of people’s pockets during a supposed cost of living crisis. What of the distribution of that cost? I expect a relatively regressive distribution. And drinks that taste worse.

As another example, one of the Behavioural Insights Team’s early projects involved offering loft cleaning services in conjunction with insulation installation, removing a hassle that was standing in the way of energy efficiency improvements. (After reading the original report on this work, this topic is deserving of another post.) Yet, in line with previous research, gas use rebounds to original levels within two years of loft insulation installation (Peñasco and Anadón, 2023). Again, this might just be thought about as second-order effects rather than complexity, but here we have seemingly simple interventions failing to achieve the desired objective.

Taking complexity seriously and seeing the system also requires thinking about ourselves. What is the process by which our work results in change? Even this is not simple. Stefan Della Vigna and Elizabeth Linos analysed the many pre-registered trials conducted by the Behavioural Insights Team in North America (full credit for transparency). In a paper published in Econometrica (DellaVigna and Linos, 2022) they demonstrated that although the effects of ‘nudges’ in the field were smaller than those in academic publications, they were real and would in many cases pass a cost-benefit test. A second paper in the Journal of Political Economy (DellaVigna et al., 2024), however, is somewhat depressing. There was no link between the evidence from the trial and implementation. We have what seems a simple lever - identify those interventions that work - and yet we don’t see this down the line in the outcomes that matter.

And here’s one further dimension of complexity that should be considered. We’re working on a lot of objectives. Look at the bodies of work focused on gender equity, retirement savings, education, and the like. Achieving these objectives have second order effects. How do they affect each other? Does encouraging female participation in STEM increase the gender wage gap? Does encouraging paternity leave affect productivity or family income? Does encouraging university attendance among low-socioeconomic status increase inequality (when they drop out or end up in a lower paying job than a trade)? Some of these might be easy to measure. But some of the interactions are likely beyond us.

So, the question I have is, should we take a message of greater humility from “seeing the system”? (Humility is one of the principles in the manifesto - but this comes from a different foundation.)

No view from nowhere

As an outsider reading the manifesto, the question I kept asking was “what is the objective?”. (I asked that in my comments on the draft manifesto too!)

If the recipe in the manifesto is followed, what would be the measure of success? The manifesto contains some general statements about applied behavioural science fulfilling its potential. I have no idea what fulfilled potential looks like. The ten proposals are largely quiet about what the manifesto is trying to achieve, outside of the explicit “Data Science for Equity”. I”ll come to that proposal later.

Similarly, what are we trying to achieve as behavioural science practitioners? This is a big question, but it’s fair to ask it of a “manifesto”. What are the consequences for the subjects of our work - citizens, customers, employees - from our interventions as applied behavioural practitioners, and how might the manifesto shape these outcomes if the manifesto’s proposals are implemented?

The point of the manifesto where the question of objective stood out most to me was in the “No view from nowhere” proposal. The summary of this proposal states:

Cultivate self-scrutiny, find new ways for the subjects of research to judge researchers, and take actions to increase diversity among behavioural scientists and their teams, such as building professional networks between the Global North and Global South.

Again, let me give my summary of that principle from the broader text. We don’t come to work with a blank slate. We bring assumptions. We bring values. Gender, race and sexuality influence our viewpoints. And so on. Because of this, we cannot view a situation from nowhere. These assumptions and values are always there. This problem is relevant as behavioural science practitioners are homogeneous. Few teams come from the “Global South”. Our research subjects have traditionally represented only a small fraction of the global population. As a result, we should give more scrutiny to our starting points and build diversity among data scientists and their teams. The call to increase diversity notes that we need to increase diversity “of several kinds”. Directly mentioned is increasing collaboration with the Global South and increasing ethnic and racial diversity.

Every time I see a call for diversity, I wonder what kind of diversity. And there is one specific type that isn’t questioned in the manifesto.

Suppose I was to ask a set of behavioural science practitioners the following questions (excuse their Australian flavour - I’m sure you can come up with versions for whatever country you wish):

- Who voted “No” in the referendum to amend the constitution to give a “Voice” to Indigenous Australians? (At one stage, the presentation was scheduled for the weekend before this referendum. And despite 60% of the Australian voting population rejecting the proposal, I am still to meet even one person in my professional world or town where I live who has openly stated that they voted no.)

- Relatedly, should we have an indigenous land acknowledgement at the start of every meeting?

- Who voted Liberal at the last Federal election? (The Australian conservative party.)

- Who believes there are only two sexes?

- Should there be a sugar tax in Australia?

I am not asking for a show of hands, but I suspect a skew in a specific direction. And that is largely reflected in the types of projects that applied behavioural practitioners work on. Equity. Diversity. Climate. The sins of the lower classes.

We work on sugar taxes in soft drinks when a large flat white has more calories than a can of Coke. (Products with more than 75% milk are excluded from the UK sugar tax.) I can’t find a serious mention of the effect of the sugar tax on taste. We work on net zero rather than energy abundance. We work on how can we get more men to take paternity leave to close the gender wage gap rather than ‘What is the optimal level of paternity leave and how can we support it’? (Given the most credible evidence on the gender gap points to a motherhood penalty from time out of the workforce (Goldin, 2014), are we trying to convert the motherhood penalty into a family penalty?) There’s hardly any questioning of whether this is even a policy issue where income is shared within a household.

The omissions also stand out. We rarely work on projects to boost productivity or economic growth. For all the talk of “libertarian paternalism”, I’m not aware of a single example of a behavioural team working hard to remove regulation and replace it with good behavioural design? Where is the push to move to a voluntary superannuation system in Australia, where we let people have their superannuation if they want it, with a behaviourally designed system to support their savings? Applied behavioural science is simply paternalism.

Here’s a final example. Many Australian women fail to meet their fertility intentions (for example, see Wilkins et al. (2021) and a summary of the report in the Conversation). This is not just an Australian phenomenon (e.g. Guzzo and Hayford (2023)). There is also considerable evidence that people don’t understand how early in life fertility starts to decline (e.g. Hammarberg et al. (2013)). Is there a project to help people to overcome this shortcoming? Contrast this to the volume of work on retirement savings.

Putting these examples together, there is a lack of intellectual diversity in the behavioural science world, and this is reflected in the work that we do. Further, there seems to be little interest in rectifying this. We’re only calling for the types of diversity that don’t challenge our world view.

Data Science for Equity

The third proposal I will briefly discuss, “Data Science for Equity”, is a view from somewhere very specific. The summary in the Nature Human Behaviour paper reads:

Use data science to identify the ways in which an intervention or situation appears to increase inequalities and introduce features to reduce them. For example, groups that are particularly likely to miss a filing requirement could be offered pre-emptive help.

I take the choice of the word “equity” as deliberate and coming with a meaning different to equality. Equity is about outcomes, not equality of opportunity. On my previous point about diversity, I’m not sure a more intellectually diverse team would have chosen that word. Think of all the things behavioural science could be achieving: productivity, happiness, financial wellbeing, economic growth, sustainability. Why single out equity?

That this proposal is “data science” and not “behavioural science” for equity is also interesting. It seems somewhat narrow to highlight one particular tool.

But the question I want to flag concerns trade-offs. When you choose a specific objective, what are you are willing to trade-off to achieve it? Absent trade-offs, the objective has no teeth. How does it guide choice of problem (including what problems you won’t work on)? What does it imply for choice of intervention and measurement of success?

The example offered in the above summary doesn’t provide much guidance. Helping people who might miss a filing requirement is innocuous. Assuming a small cost of a reminder or prompt, there’s no real trade-off here.

So let’s pull out a cartoon example. You discover that abolishing advanced math classes reduces the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous students, largely by reducing the performance of the top cohort. Is this the equity you want to achieve?

Maybe not, but it’s not clear from the proposal. And if it’s not, where would we draw the line? Do we want to prioritise problems that lift the bottom but harm no-one else? (Is it now data science for Pareto improvement?)

And this brings me back to my previous question about objectives. Should our goal be equity? Or should it be to bring out the best in us in our own way?

I don’t expect Hallsworth to have the complete answer in his manifesto, but I’m not sure I get any useful guidance from this objective of equity.