Hungry judges

The media and blogosphere has dedicated plenty of column and blog inches to a recently published study by Danziger and colleagues on how parole rates by Israeli judges vary through the day. From the abstract:

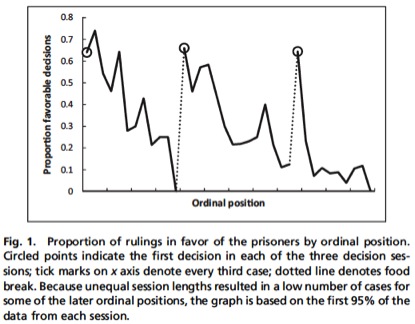

We record the judges’ two daily food breaks, which result in segmenting the deliberations of the day into three distinct “decision sessions.” We find that the percentage of favorable rulings drops gradually from ≈65% to nearly zero within each decision session and returns abruptly to ≈65% after a break. Our findings suggest that judicial rulings can be swayed by extraneous variables that should have no bearing on legal decisions.

The following chart provides a good illustration.

Of other factors to influence the judges’ decisions, only history of re-offending and the presence of a rehabilitation programme were found to have a statistically significant effect. The crime committed, time served, ethnicity or sex did not affect parole probability.

The cases were presented to the judges in effectively random order and they did not know which case was coming next. The time of the hearing was generally dependent on the time of arrival of the prisoner’s lawyer. As a result, the pattern of declining parole rates during a session was not due to easier cases being heard first.

The response in the media and blogosphere is that this is another example of people being irrational and that judges are subject to the same biases as everyone else. The authors suggest even wider implications:

[W]e suspect the presence of other forms of decision simplification strategies for experts in other important sequential decisions or judgments, such as legislative decisions, medical decisions, financial decisions, and university admissions decisions.

Having now identified the effect of this bias, what do we do? Jonah Lehrer suggested that “it’s imperative that we make judges aware of these tendencies, so that they can take steps to reduce their effects.” Ed Yong quotes Nita Farahany of Vanderbilt University as saying that “improvements in the justice system may likewise require that society acknowledge the effects of biological contributions to legal decision-making.”

Having stewed on it for a month, I am wondering whether we should simply remove the judges altogether - and replace them with a set of decision rules. This would have two effects - the first of which is that it would end the problem created by the meal breaks and hungry or tired judges.

More importantly, it could result in the right decision being made more often. In discipline after discipline, evidence is emerging that simple decision rules or algorithms can outperform expert decisions. Take the examples in Ian Ayres’s Supercrunchers, where he talks of how decision rules have outperformed wine experts in predicting wine quality, legal experts in predicting Supreme Court decisions and doctors in predicting heart attacks. Most relevantly, Ayres discusses the increasing use of sentencing guidelines in parole decisions. As people can’t seem to let completely go of judicial discretion, there is always some space left for it. But as Ayres notes:

Parole and Civil Commitment boards that make exceptions to the statistical algorithm and release inmates who are predicted to have a high probability of violence tend time and again to find that the high probability parolees have higher recidivism rates than those predicted to have a low probability.

As an extra thought, the next time a politician seeks to legislate specific sentences instead of relying on judicial discretion, they should pull this study out and suggest that judges are not the rational people we hope they are.