John List’s The Voltage Effect: A review

Over a decade ago when I started reading the behavioural economics literature, John List quickly became one of my favourite academics. Whenever I read an interview with List he always seemed to ask great, critical questions. He was rarely happy taking others’ assumptions as given. I saw him as someone who, on hearing “in my experience….”, would be the first to say “Should we run an experiment?”.

My impression of List has somewhat changed in the last year. His Twitter posts seem more focused on promotion than shooting down weak ideas. There goes my image of List as a cynic! But I also suppose that’s the angle you need to take when you are pushing a new book.

That book is The Voltage Effect: How to Make Good Ideas Great and Great Ideas Scale.

The term Voltage Effect comes from the literature on implementation science. The “electric” potential of what appears to be a promising intervention will often dissipate when rolled out into the real world. In List’s case, this “voltage drop” occurs between the initial pilot of an economic intervention and the full-scale rollout of the intervention. Why are those rollouts so often disappointing despite the initial promise?

List seems the right person to answer that question. List pioneered the use of field experiments in economics. He was the Chief Economist for Uber, then Lyft and now Walmart. (I believe the Walmart role post-dates this book.) He has a rare catalogue of field trials and implementation experience.

But rather than being the author of this book, I would rather see List in another role. I’d love to read a review of this book by ….. John List.

Why?

In the book’s first half, List describes five problems that can cause voltage drops. In the second half, he gives four “secrets” to high-voltage scaling. I agreed with most of his high-level points in the first half and saw some potential in those in the second.

But the problem is that these points aren’t drawn from experiments themselves. They come from List’s experience.

John List’s forte is that he runs experiments to see if things are true. Throughout the book, List has stories where someone makes a claim, and List responds, “Let’s run an experiment”. But when he tries to talk about what works at the level above the experiment - the book’s theme - we have to listen to John List say, “Well, in my experience …”. I respect List’s experience but kept thinking, “Maybe that’s true, but I’m not convinced … could we run an experiment?”.

The five problems that cause voltage drops

List’s five barriers to scaling all make sense. Watch out for false positives. Know your audience. Make sure the ingredients to your implementation can scale. Consider spillovers. And understand what scaling will cost.

On the first barrier, List notes that many ideas might seem promising during trials. But the statistical frameworks that we use can lead to false positives. Don’t be afraid to use a second trial or staged implementation to check that the first trial wasn’t a fluke. You should seek independent replication of your own work. And consider the incentives of those who are pushing any particular idea.

I agree with this advice, although perhaps with a different emphasis. List doesn’t give much ink to the replication crisis or mention that the behavioural science literature is littered with false positives. Some of the literature you’re using as inspiration is likely rubbish. List does recognise scientific misconduct - telling the story of Brian Wansink - but doesn’t hint at how untrustworthy much of the literature is, even in the absence of fraud.

I am also sceptical of List’s reasons why false positives can cause such problems. One reason he gives is confirmation bias, which prevents us from seeing evidence that might challenge our assumptions. He even gives us an evolutionary spin:

This tendency might appear counter to our own interests, but in the context of our species’s long-ago Darwinian history, confirmation bias makes perfect sense. Our brain evolved to reduce uncertainty and streamline our responses. For our ancestors, a shadow might have meant a predator, so if they assumed it was one and started running, this assumption could have saved their lives. If they stopped to gather more information and really think about it, they might have ended up as dinner.

I’m not sure what is being described in that paragraph is confirmation bias. But more notably, we seem to have entered “drop a bias” territory: see a behaviour and tell a post-fact story about what bias is supposedly causing this problem. List tells us about the bandwagon effect, where we jump on board with others, effectively leaving the selection of ideas to a few people rather than the collective group. We hear about sunk cost bias. List even shoehorns the winner’s curse into the story, a phenomenon in common-value auctions (an auction where the auctioned good has the same value to everyone) whereby the winner tends to overpay. The winner will tend to have the most optimistic estimate of the value of the good - and if you’ve got a higher estimate than everyone else, there’s a decent chance you’ve overestimated. How does this apply to scaling false positives? After reading the section several times, I’m not sure.1

And where’s the experimental evidence that these biases are driving the problem? At this point, List’s stories feel loose.

List’s second barrier to scaling relates to” knowing your audience”. This is essentially a story of heterogeneity in your sample and the population in which the intervention will be rolled out. How broadly will your intervention work when you move from your trial sample to full-scale implementation? This includes a perspective across time: your current and future audience might differ. Sound advice.

The third barrier is whether all the elements of the intervention can scale. Is the pilot representative of the circumstances at scale? For example, if your educational intervention pilot involves all of the good teachers, it likely won’t work when it scales and the weaker teachers become involved. If you are monitoring compliance in the pilot - that is, the experimenters are watching - failure to monitor during the rollout may result in a substantial voltage drop. I have seen this myself, where the deck was stacked in the pilot.

To illustrate this point, List tells the story of the restaurant chain Jamie’s Italian. Initially, the key to the restaurants was the simple ingredients and recipes, easily replicable at a larger scale. Brand and fame can also scale. But later on the unscalable part of the operation - Jamie Oliver himself - became stretched, and the whole enterprise came down.

I understand why people include stories like this in pop science books. I use examples like this myself. But this involves going out on a limb, ascribing causes to events that aren’t backed by a robust analysis of causation. We’re telling stories.

List’s story involves the new managing director of the enterprise being described as “woefully unqualified”. But what’s the metric for “unqualified” beyond the post-fact assessment based on the chain’s failure? Is this just the (negative) halo of the outcome being extended to those involved? (There’s me dropping a bias…) I’ll return to this point of storytelling in a bit.

The fourth barrier is the presence of spillovers. List has a nice story from Uber to illustrate. An initial trial of giving $5 coupons to a group of Uber riders was a success: the riders used Uber more, with the increased earnings more than offsetting the cost of the coupons. However, when rolled out at scale, the earnings increase did not materialise. The spike in demand caused by the coupons caused an increase in fares and wait times, which reduced demand.

The final barrier concerns the ultimate cost of scaling. Sometimes expected economies of scale don’t materialise. There simply might not be enough of what you need at a reasonable cost: for example, what is the cost of hiring enough “good” teachers to implement at scale?

The four secrets to scaling

From the barriers List then moves to the secrets to success. I was more ambivalent toward the four secrets, but they still have some wisdom.

The first is having incentives that scale. This isn’t just about the size of the incentives, but considering how they can be made more powerful (e.g. by using loss aversion) and whether non-monetary incentives such as social norms can be leveraged. Most of this is relatively uncontroversial material. It is, after all, the reason why there has been some success in applied behavioural economics. But the following claim stood out:

[T]he fact that human psychology doesn’t vary much across groups (most people experience loss aversion to a similar degree, and nearly everyone cares about their social image) makes this type of incentive strategy highly scalable. In contrast, the level of financial rewards necessary to incentivize one’s employees will vary widely from person to person, and for some might be unduly high.

I couldn’t locate in the book the reference supporting this claim. And it doesn’t align with any of the studies I might look to on this point. On variation, Joe Henrich and friends (2001) showed substantial variation across societies in trust and reciprocity in economic games. Harrison and Rutström (2009) showed evidence for a mix of “economic” and “behavioural” decision makers in a group of experimental subjects. The whole concern about experiments on WEIRD people is due to the potential for variation across cultures.

To be honest, I believe that the worry about the generalisability of experiments using WEIRD subjects is overblown (particularly compared to the other dimensions we should be worrying about). The Many Labs 2 project (Klein et al., 2018) found little heterogeneity across cultures as to which effects were replicable. But I would expect an equivalent experiment using incentives would similarly replicate across cultures.

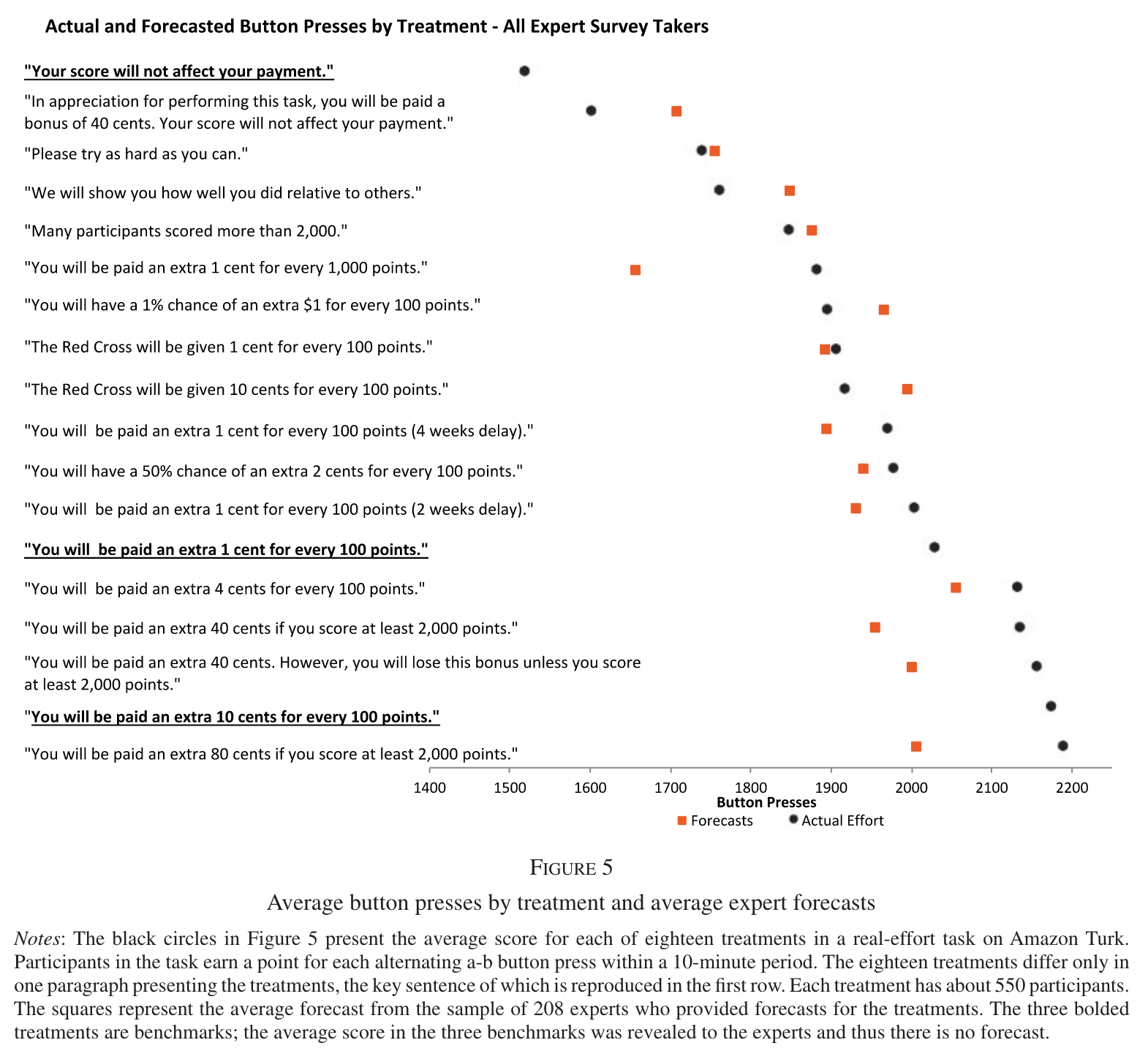

On the power of psychological interventions versus incentives, ideally, we’d want a suite of studies comparing the two directly. List has a couple of studies where the psychological intervention outperforms the incentive. But it’s easy enough to find studies going the other way. Here’s one from DellaVigna and Pope (2018). In their particular (artificial) context, incentives were the more powerful motivator and effort scaled with the incentives. Amusingly, the “experts” predicting the results also underestimated the power of the incentives.

Putting this together, I’m sure there are cases where a behavioural strategy will outperform a simple monetary incentive. But I don’t buy the general claim about variability or scalability.

List’s second secret seems a no-brainer, to an economist at least. When calculating costs and benefits, look to the margins. Ask what benefit the last dollar spent gets you. Don’t simply compare total costs and benefits as, even if the total benefits are greater, you could be spending less for greater net benefit.

The third secret is optimal quitting. Don’t sink more time into the wrong idea. We get stories about PayPal and Twitter emerging from other failing strategies, and List’s own decision to give up on a professional golf career. We get another dose of biases here, including sunk cost bias and ambiguity aversion, but it’s sound advice all the same. The challenge is, as List highlights, determining the optimal point to quit. It’s hard.

The chapter on the fourth and final secret, the need to scale culture, opens with the story of two Brazilian villages, Cabuçu and Santo Estêvão.

Cabuçu is a small fishing community in which the men fish in groups of three to eight. This teamwork is needed to manage the boats on the choppy Atlantic waters, set the nets and pull in the large fish. A single fisherman would fail.

Santo Estêvão sits inland of Cabuçu on the Paraguaçu rover. The villagers from Santo Estêvão catch small fish alone on the calm waters.

List and colleagues ran games in the two villages to test whether their style of fishing, shaped by the environment each found themselves in, was reflected in their level of trust and cooperation. They found that the villagers from Cabuçu proposed more equal offers in the Ultimatum game, contributed more in public goods games and invested more in the trust game (and sent back more). They also donated more to charity. The habit of cooperation in their work flowed over into other domains.

List leverages this story into one of scaling up workplace cultures. How the organisation works will affect the values underlying that organisation.

This leads to the case of Uber and Travis Kalanick. The story, in a nutshell, was a series of scandals in early 2017 - claims of sexism and sexual harassment, a lawsuit by Waymo alleging the theft of trade secrets, a video of Kalanick berating an Uber driver who challenged him on driver compensation, and most damaging, the revelation of software designed to evade law enforcement and regulators - ultimately led to Kalanick resigning as CEO.

List pins this series of scandals on Uber’s culture. Kalanick believed in a “meritocracy” where the best ideas should win. For those ideas to emerge, Uber required a combative culture. However, as Uber scaled that combative culture no longer did. Rather than surfacing the best ideas, ideas succeeded based on who was the loudest or the best internal politician. When the best ideas and people ceased to rise to the top, staff lost trust in leadership and the behaviour of staff shifted.

Ultimately, when Kalanick exited, he conceded these flaws. Kalanick wrote:

I favored logic over empathy, when sometimes it’s more important to show you care than to prove you’re right, … I focused on getting the right individuals to build Uber, without doing enough to ensure we’re building the right kind of teams.

and

Ultimately, we lost track of what our purpose is all about—people. We forgot to put people first and as we grew, we left behind too many of the inspiring employees we work with and too many of the amazing partners who serve our cities …. Growth is something to celebrate, but without the appropriate checks and balances can lead to serious mistakes. At scale, our mistakes have a much greater impact—on our teams, customers and the communities we serve. That’s why small company approaches must change when you scale. I succeeded by acting small, but failed in being bigger.

This might all be right, but I find it amusing hearing a story about how the founder of a company, personally worth over $4b, stuffed up in creating their (as of the day of writing this paragraph) $87b market cap company by having the wrong culture. I am sure Kalanick could have done better, but I’m also sure he could have done worse. (Lyft, the company to which List moved after Uber, has a market cap of $3.8b.) Would a more toned-down Kalanick have been able to build Uber? Could someone with the personality to drive the smaller company simply transition as required? And is it even optimal to do so?

There’s a lot of “halo effect” storytelling going on here - problems emerge, must have been the culture, a disaster waiting to happen. And yet by the measurable outcome, arguably the number one measure for a company, Uber is a massive success for Kalanick. It reminds me of those criticizing the range of choice on Amazon as paralysing consumers with excessive choice. And what would happen if you tried to get the fisherman of Santo Estêvão to work in teams? Maybe they’d cooperate more in economic games, but would they do better at feeding their families?

Concluding note

As is typically the case for posts on this blog, most of the above is picking at the seams. But there is a lot to like in the book and some good advice. Thinking about each of the barriers and secrets should improve the experiments you run and how they scale. I’m just not sure all of the stories List tells are true.

Other thoughts lying around

In his discussion of confirmation bias as a reason why false positives can cause such problems, List states “Because we have limited brainpower to process all of this, we use mental shortcuts to make quick, often gut-level decisions. One such mental shortcut is to essentially filter out or ignore the information that is inconsistent with our expectations or assumptions.” That second sentence is almost the opposite of perceptual control theory / predictive processing, which is based on the idea that our brain responds to differences from our expectations.

List states: “If that suggestion sounds outrageous, consider an explosive study conducted by researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine in 2016, which estimated that more than 250,000 Americans die each year from medical errors, making such errors the third-leading cause of death behind heart disease and cancer!” This stat is rubbish and there are a pile of academic and other papers pulling it apart. Here’s one

List writes: “Kahneman and Tversky demonstrated that as a result of this human tendency, we make all sorts of harebrained decisions. For instance, when housing prices fall after a boom, sellers attempt to avoid the inevitable loss by setting a higher asking price—often higher than their home’s current value—and in turn the property sits on the market for a longer period of time than it otherwise might.” Genesove and Mayer (2001), who I assume is the source of List’s claim, also found that those people receive a higher sale price. Sounds sensible rather than harebrained to me, particularly when other evidence suggests people sell too fast (such as Levitt and Syverson (2008)).

List jumps on the diversity bandwagon: “I mean diversity in all senses: race, sex, age, ethnicity, religion, class background, sexual orientation, gender identity, neurotype, and other characteristics. Diversity in people’s backgrounds equates to cognitive diversity when they are together, which produces not just greater innovation but also greater resilience.” List wants all these types of diversity to achieve “cognitive diversity”, but doesn’t mention cognitive diversity itself. We could measure it! And as usual, you seldom see “political views” on the list. Among the many disciplines and groups I have worked with (law, economics, data science, regulators, policy advisers, environmental campaigners), the behavioural scientists and behavioural economists would be the most cognitively uniform group.

References

Footnotes

A related point might be that if you are running many comparisons, the most promising will likely have an exaggerated effect size, but there are simple statistical methods (that I expect people like List would be using) to correct for this.↩︎