#Plot of probability weighting function using ggplot2

library(ggplot2)

#Define probability weighting function

prob_weight <- function(p, alpha){

exp(-(-log(p))^alpha)

}

#Create data frame of probabilities and weights

prob <- seq(0, 1, 0.001)

prob_df <- data.frame(prob = prob, weight = prob_weight(prob, 0.6))

#Plot

ggplot(prob_df, aes(x = prob, y = weight)) +

geom_line() +

#Add labels

labs(x = "Probability", y = "Weight")Using generative AI as an academic - July 2024 edition

I first wrote a version of this post in April 2023. A lot has changed since then in both the tools and how I use them.

As was the case then, if you want a sense of the frontier, others such as Ethan Mollick will give you a better flavour. But if you’re after some practical examples, you might find this useful.

My toolkit

I use multiple tools, switching between them depending on the task and comparing the responses. I want to gain a sense of the frontier.

As an academic, I gain free access to Github Copilot. (Students can also get free access.) CoPilot provides code suggestions in coding environments. But while badged this way, CoPilot also provides text suggestions more broadly. To access CoPilot, I write markdown documents in Visual Studio Code or RStudio. (For those who want more specific guidance on how to set this up, I’ve added that at the bottom of this post.) If you use CoPilot in Visual Studio Code you also gain access to Copilot Chat.

I also work with ChatGPT Plus and Claude Pro open in a browser. I subscribe to the Pro/Plus version of both: it is worth it for the superior tools. As you’ll see from the below, I use them all the time, although more recently I lean toward Claude.

I run some other large language models locally on my computer using Ollama. I do this more to get a feel for them than for current utility. Most of my recent experimentation has been with Llama 3. I use these models via the command line or the CoPilot plugin in Obsidian.

I also subscribe to ElevenLabs for its voice-generation capabilities. More on that below.

I’ve experimented with other tools, but they haven’t yet formed a large part of my workflow. I don’t use Bing much, except for images if ChatGPT isn’t giving me what I want. I like that it gives four images for every prompt. I experimented with Google Gemini but haven’t found a reason for it to supplant the Claude plus ChatGPT combination. I revisit it every month or two to see whether I should add it to the mix.

Thinking

- Efficiency gain: uncertain

I am increasingly using Claude and ChatGPT as interactive rubber ducks. When thinking through something new, I’ll often state my thoughts and ask for comments. I’ll often ask them to explain a concept to me, then I will ask follow-up questions. Sometimes I’ll do this in ChatGPT with voice mode when I am walking. I know that I’m not getting 100% accurate information, but I wouldn’t talking to a friend either.

Similarly, after reading an article and forming my own views on its message, strengths and weaknesses, I’ll ask Claude or ChatGPT their views. I find this can be hit and miss, but on net worth doing. Sometimes the description is spot on, and the critiques hit points I haven’t thought of.

Finally, if I have a technical question, I’ll ask before googling. It’s faster and, I would say, more accurate than the top Google hits.

Coding and data analysis

- Efficiency gain: 10x

- Quality gain: 50%

Despite spending a lot of time in R, I am a crap coder. As a result, my typical approach is to write a comment and let CoPilot do the first cut of the code. I will then tweak the code until it is in shape. That tweaking isn’t manual tweaking either. If there is an error or problem that I can’t resolve, I’ll use CoPilot Chat to get a solution. Chat will usually provide code solving the problem.

CoPilot is also great in helping me understand someone else’s code. I’ll highlight sections and ask CoPilot Chat to explain what it does. Often, I’ll paste poorly documented code into Claude or ChatGPT and ask it to write comments. Further, If the code looks overly complicated, a request to simplify often yields good results. (I’ve been asking ChatGPT to review some of my old code recently. I’m a bit embarrassed at how much more efficiently I could have written it.)

One large benefit has come from cross-language translation. Last year I wanted to reproduce the results in Berkeley Dietvorst’s Algorithm aversion: People erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. Data and the code for analysis were available on ResearchBox. The problem was that the code was in Stata, and I have no desire to learn Stata.

I pasted the Stata code into ChatGPT and asked for a conversion to R. What I received was 90% of the way there. Initially, there was an error, but pasting the error into ChatGPT gave me the solution first shot. I then tweaked a couple of the variable manipulations and specified that some of the t-tests were paired t-tests. That was it. In less than 10 minutes I had code that reproduced exactly the results from Study 1. I’ve now done this translation dozens of times when examining and reproducing studies by others.

I’m increasingly asking ChatGPT and Claude to provide me with working programs. For example, I am building a website with an underlying database and model for predicting AFL games. (I wanted to experiment with how far I could go with these tools.) I obtained a web interface and underlying code from Claude to access the database. I used ChatGPT for the first version of the predictive model. I’m now playing with the details, but the core is there. I wouldn’t even attempt it without these tools.

Data exploration

- Efficiency gain: 2x

Any time I am about to work with new data, confidentiality permitting, I’ll give the data to ChatGPT and ask about it. I’ll start generally: “tell me about this file”. Then I’ll work down to the details and ask for basic visualisations and analysis. Finally, I’ll export the Python code (or ask for an R version of the code).

Ever since the Dan Ariely car insurance data fraud, which is obvious from a simple plot, I’ve made it a habit of looking at the data before jumping into analysis (which I didn’t do as often as I should have in the past). It’s surprising how often I find that something is not quite right or as expected. Having ChatGPT on hand makes this first step quick and easy.

Extracting pdf data

- Efficiency gain: 10x

This is a small one in that I don’t need to do that often, but it’s a massive time saver. If there is a large table in a PDF, I ask ChatGPT to output it as a CSV. Recently, I had data spread across half a dozen PDFs in poorly formatted tables. I used ChatGPT to combine and arrange the data. I check the accuracy as I don’t fully trust ChatGPT, but the accuracy is typically great, saving me a lot of time.

Writing

- Efficiency gain: 20%

- Quality gain: 10%

When I first started using GitHub CoPilot, I would have it on whenever I was writing. I would receive suggestions as I typed. Today, I generally turn it off when writing a first draft. The distraction in filtering suggestions was too costly, and I was worried about getting dragged in random directions.

However, I use Claude and ChatGPT a lot to improve my writing. When I’m having trouble getting a sentence or paragraph right, I’ll often hand it over and ask for 10 possible rewrites. Similarly, I will ask for simpler, shorter or more conversational text. I’ll rarely take a rewrite as provided, but it often gives me a word or turn of phrase that does the job.

Lecture notes

For more mechanical lecture notes, there are some clear gains. The notes for my undergraduate behavioural economics subject (which you can access here) were produced with CoPilot assistance.

Here are a few instances where CoPilot has been useful.

Often the notes include a statement of a concept followed by a step-by-step example or illustration. The gain comes when you’re writing those steps.

For example, in a section about decision making under risk, I might write:

Bill is a risk-averse agent with utility function u(x)=\text{ln}(x) and wealth of $100. He is offered a 50:50 bet to win $100, lose $50.

Will Bill accept the bet?

If I write the first couple of words of the answer “First, we calculate…”, CoPilot is away.

First, we calculate the expected utility of each option. The expected utility of the bet is:

```{=tex}

\begin{aligned}

EU(\text{bet}) &= 0.5 \times u(100) + 0.5 \times u(-50) \\

&= 0.5 \times \text{ln}(100) + 0.5 \times \text{ln}(50) \\

&= 4.259

\end{aligned}

```The expected utility of not taking the bet is:

```{=tex}

\begin{aligned}

EU(\text{no bet}) &= U(100) \\

&= \text{ln}(100) \\

&= 4.605

\end{aligned}

```As the expected utility of the bet is less than the expected utility of not taking the bet, Bill will not accept the bet.

Not bad for a few seconds of work. For those unfamiliar with the mathematical notation, this is \LaTeX, which renders into nice equations like this.

\begin{aligned} EU(\text{bet}) &= 0.5 \times u(100) + 0.5 \times u(-50) \\ &= 0.5 \times \text{ln}(100) + 0.5 \times \text{ln}(50) \\ &= 4.259 \end{aligned}I might beef this up with a better explanation, or paste the question into ChatGPT directly, where I tend to get more detailed answers. CoPilot has done OK with the math here - the logs are correct!

CoPilot is also great when I’m doing repetitive tasks such as describing the elements of an equation or diagram. Start describing the first element and it might give you the rest. And if you write a point followed by “Conversely, …”, CoPilot is often on the money.

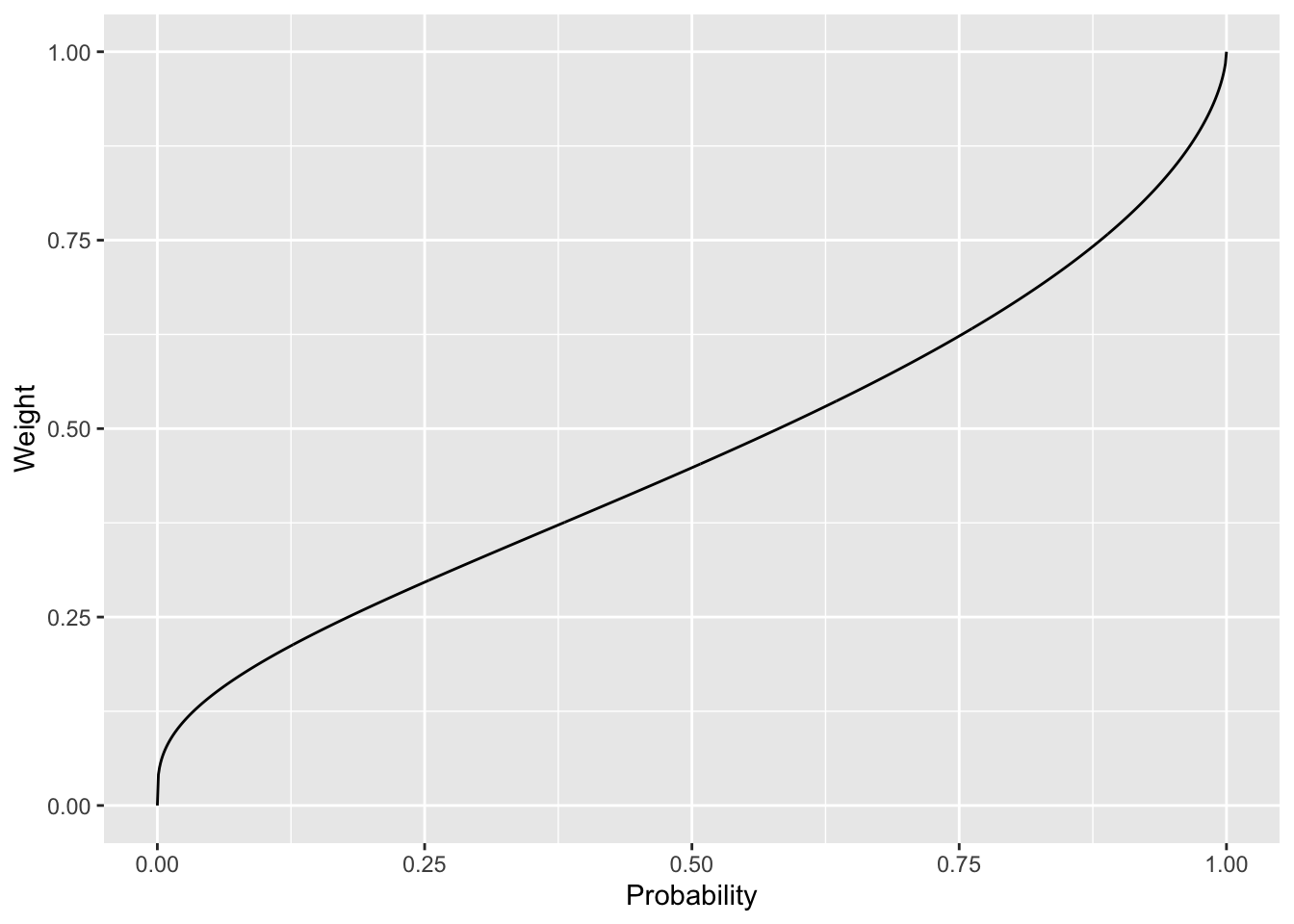

I also use CoPilot with ggplot to produce graphs for the notes. When I wanted to generate a chart showing a probability weighting function from prospect theory, I created an R code block and typed a comment:

#Plot of probability weighting function using ggplot2

Here’s the result that ChatGPT produced with the diagram rendered below:

Exactly what I wanted. When I implemented this in the notes, I only tweaked the style and added a 45-degree line.

CoPilot’s offering uses Prelec’s (1998) probability weighting function. Whether it picked that up from earlier text in my notes or just gave the most common function for probability weighting, I don’t know, but it’s what I would have used if doing it manually. However, in writing this post I wasn’t able to replicate what I did when writing the lecture notes. I got better results in the lecture notes themselves. A few paragraphs about probability weighting before I ask for the code generated better results than asking for the chart straight up.

CoPilot didn’t offer this full chunk of code at once. Each comment was offered, then the piece of code after it, one after the other. But the only work I did was writing the first comment and pressing tab several times as each succeeding comment or chunk of code was suggested. (CoPilot has certainly increased the level of comments in my code too.)

Writing organisational fluff

Work in any decent-sized modern organisation and you will have to write some level of fluff to satisfy the higher-ups, clients, government requirements and the like. I am hopeless at those tasks. I have to invest heavily to make fluff sound decent.

My approach to these exercises depends on the degree of pointlessness.

If the task relates to a process that will have zero impact on what anyone will do, I simply give the task to ChatGPT, let it do the first cut and then tweak as required. One or two sentences of guidance often get you 80% of the way there.

If I think there is a positive benefit to the task, or it’s for public consumption, I’ll be more proactive first up. I will write a rough draft, not caring much about the writing but making sure the concepts I want to include are there. It might be in dot points. Then I’ll ask ChatGPT for a version that is “clearer”, “simpler” or “better written” or “for a ten-year-old”.

Recently, I needed to describe how a program met a set of quality criteria. I uploaded some documents describing the program and a pdf that contained the criteria (in a table). I then asked Claude to provide me with short paragraphs describing how the program met the criteria. Some mild tweaking and I was there.

Generating quiz questions

- Efficiency gain: 3x

One of the best ways to learn is to be tested. As a result, I offer students in my undergraduate subject a series of practice quizzes that they can work through.

It’s hard work to generate questions in bulk, and I struggle to generate plausible-sounding but incorrect answers to multiple-choice questions. I now ask ChatGPT to generate them. I upload my subject notes and ask that they be used as the basis of the questions. In the prompts, I vary in the specificity of the questions. “Give me 20 multiple choice questions testing the concept of loss aversion.” “Give me 20 multiple choice questions testing prospect theory.” Out of each batch, only a few will be suitable. But by tweaking my instruction by, say, describing the level of the students (undergraduate) or more explicitly defining the concept, it doesn’t take long to get 10 or so good questions.

I have also used ChatGPT to generate question ideas for assessable quizzes and exams. That exam is a closed-book AI-invigilated exam, so is less vulnerable to someone simply feeding the questions back to ChatGPT. One helpful approach was to upload some previous exams plus my subject notes and ask for new exam questions at the same level of difficulty or on the same concepts.

AI-voiced lectures

- Efficiency gain: 10%

- Quality gain: 50%

Last year I decided to base my undergraduate behavioural economics subject around short pre-recorded videos, interactive online seminars and tutorials. To produce the videos I wrote scripts, which also form the subject notes. I read the notes accompanied by slides.

There are three pain points in this exercise. First, I speak too fast (even when I think I’m speaking slow) and I enunciate many words poorly. Second, recording takes a lot of time. I rarely get a two to five-minute video in a single take that I’m happy with. Third, if I want to tweak the recording, I need to either re-record solid chunks of text or fiddle around with video edits.

So, why not get an artificial voice to do the speaking? When I wrote my last post, AI-voiced lectures were the future. It’s now a core part of my subject delivery.

I experimented with Murf.ai, Speechify, play.ht and ElevenLabs. Initially I used Murf.ai to make some videos, as it allowed me to pair slides and text easily. I could also integrate with Google Slides. However, the voices sound a bit robotic, so I currently use ElevenLabs, even though all I get is an audio file. ElevenLabs has fantastic voices. Even a hint of AI voicing gets a negative reaction from students, so voice quality needs to be my primary criterion. If the Murf.ai voices improve and Eleven doesn’t develop video integration, I may shift back.

The production process is easy. I paste the text into an ElevenLabs project chapter and render the voice. Typically, the pacing won’t be quite right, so I’ll add some commas and dashes to create some pauses. I then export the voice file and combine it with images in Final Cut Pro. I can normally create a five to 10 minute video from text and slides in less than a hour.

The fantastic part is that if I want to update a section or change a sentence, I update the script in ElevenLabs, re-render the relevant sentences, load a new voice file into the Final Cut Pro project and tweak the slide timings (if the voice edits require it). It’s fast, simple and gives me a consistently high-quality video.

ElevenLabs can “clone” your voice. I tried a quick clone on play.ht, but it gave me an American accent. On ElevenLabs, you can get a professional clone of a voice by uploading three or more hours of audio. I did that, and it sounds just like me, even with the Australian accent. Unfortunately, it comes with my faults, particularly speaking too fast. ElevenLabs doesn’t have an option to slow down the speaking outside of putting a mountain of dashes through the text. It also reflects the quality of my home recording setup and sounds a bit echoey. So, for now, I’m using one of their off-the-shelf Australian voices.

Here are two samples of the above paragraph, an off-the-shelf Australian voice and my “cloned” voice.

I’ve also started looking at options to create an AI avatar based on videos or photos of me for some parts of the videos. I’m leaving that one for the moment but can see myself revisiting it in the next year.

Accessing GitHub CoPilot

The below gives the basic steps to access GitHub CoPilot.

If you are an academic, you can sign up for (free) academic access to CoPilot at this link. If you’re not an academic or student, sign up for a free trial as described here. You’ll need a Github account to do this. The $10 a month is worth it.

Visual Studio Code is available here. (I use the Mac version.) Download and install.

Install the Github CoPilot extension into Visual Studio Code. Instructions on installing the extension are here. On installation you’ll be prompted to login to GitHub to gain access to authorise CoPilot.

Once you have done that, using CoPilot is easy. You simply type. As you type, you will be given suggestions.

The setup in RStudio is even easier. Download RStudio from here. Under Tools/Global Options is a CoPilot menu item. Enable CoPilot there. You will be asked to enter your GitHub login details to get it running.

I write in markdown (and at the moment, a flavour of markdown called Quarto). It allows me to include \LaTeX math and R computations within any document (as I have in this post). If you’re an academic stuck in the \LaTeX ecosystem, you can also write in Visual Studio Code wholly in \LaTeX. You can also just get CoPilot in Word. I’m looking forward to my university moving beyond the experimental stage and giving us access. (I took a one-month free trial of Microsoft CoPilot on the home computer, but didn’t find the time to give it a proper go.)