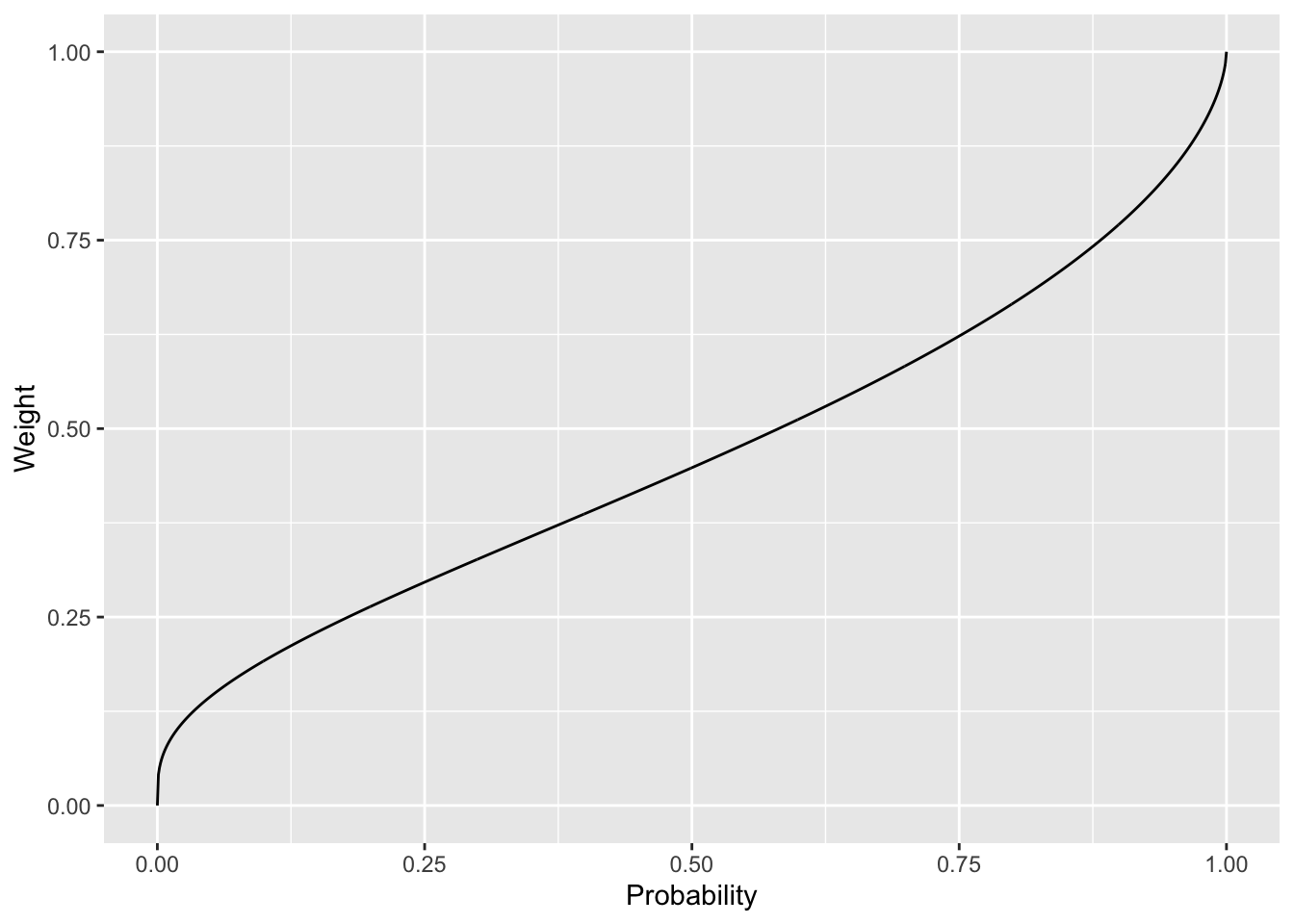

#Plot of probability weighting function using ggplot2

library(ggplot2)

#Define probability weighting function

prob_weight <- function(p, alpha){

exp(-(-log(p))^alpha)

}

#Create data frame of probabilities and weights

prob <- seq(0, 1, 0.001)

prob_df <- data.frame(prob = prob, weight = prob_weight(prob, 0.6))

#Plot

ggplot(prob_df, aes(x = prob, y = weight)) +

geom_line() +

#Add labels

labs(x = "Probability", y = "Weight")Using large language models as an academic

This post started as a draft email to my colleagues about how I was using large language models in my work to achieve some fairly large efficiency gains. I realised that this was easier to send as a blog post. And why not share more broadly?

I am a long way from the frontier in how I am using these tools. If you want to see the frontier, go read Ethan Mollick among others. But I would estimate I’m using these tools more than 95% of academics, so hopefully there is something in there for many of you.

My toolkit

As an academic, I gain free access to Github Copilot. (It’s only $10 a month otherwise.) CoPilot is badged as “your coding companion”, providing code suggestions in coding environments. But while badged this way, CoPilot also provides text suggestions more broadly, and that is how I largely use it.

CoPilot gives me access to whatever language models Microsoft is running behind it. I’m not sure if GPT-4 is available through CoPilot yet, but I would say performance on CoPilot has improved over the six months I have been using it.

To access CoPilot, I write markdown documents in Visual Studio Code. Since I started blogging (12 years now!) I have always written in markdown (and at the moment a particular flavour of markdown, Quarto). Before the emergence of CoPilot, I also used RStudio and other text editors that support markdown. But with CoPilot not available in RStudio, I’m almost exclusively in Visual Studio Code now. For those who want more specific guidance on how to set this up, I’ve added that at the bottom of this post.

I also work with ChatGPT open in a browser. If CoPilot isn’t giving me what I want, ChatGPT often will. If I can frame my requirement as a standalone question, ChatGPT tends to do a better job. But when working on a document, CoPilot’s suggestions are normally better (unless I paste the whole document into ChatGPT).

I’ve tried Bing, but find it harder work to get what I want unless I have a question for which I want references.

Writing lecture notes (efficiency gain: 10 to 30%)

I don’t find CoPilot particularly useful if I’m writing something original such as a blog post. In writing this post I wouldn’t say CoPilot has increased my efficiency at all (outside of helping me create the examples). I sometimes accepted suggestions from CoPilot, but the need to filter through the various suggestions resulted in negligible efficiency gain.

But for lecture notes, which are more mechanical, there are some clear gains. The notes for my undergraduate behavioural economics subject (which you can access here) were produced with CoPilot.

Here are a few instances where CoPilot has been useful.

Often the notes include a statement of a concept followed by a step-by-step example or illustration. The gain comes when you’re writing those steps.

For example, in a section about decision making under risk, I might write:

Bill is a risk-averse agent with utility function u(x)=\text{ln}(x) and wealth of $100. He is offered a 50:50 bet to win $100, lose $50.

Will Bill accept the bet?

CoPilot will sometimes write something like:

Can someone please help me answer the following question: “Will Bill accept the bet?”

There must be a lot of study cheat sites forming part of the training data.

But if CoPilot does that, simply write the first couple of words of the answer “First, we calculate…” and then CoPilot is away.

First, we calculate the expected utility of each option. The expected utility of the bet is:

```{=tex}

\begin{aligned}

EU(\text{bet}) &= 0.5 \times u(100) + 0.5 \times u(-50) \\

&= 0.5 \times \text{ln}(100) + 0.5 \times \text{ln}(50) \\

&= 4.259

\end{aligned}

```The expected utility of not taking the bet is:

```{=tex}

\begin{aligned}

EU(\text{no bet}) &= U(100) \\

&= \text{ln}(100) \\

&= 4.605

\end{aligned}

```As the expected utility of the bet is less than the expected utility of not taking the bet, Bill will not accept the bet.

Not bad for a few seconds of work. For those unfamiliar with the mathematical notation, this is \LaTeX, which renders into nice equations like this.

\begin{aligned} EU(\text{bet}) &= 0.5 \times u(100) + 0.5 \times u(-50) \\ &= 0.5 \times \text{ln}(100) + 0.5 \times \text{ln}(50) \\ &= 4.259 \end{aligned}I might beef this up with a better explanation, or paste the question into ChatGPT direct, where I tend to get more detailed answers. GPT-4 also tends to be better at math. (CoPilot has done OK here - the logs are correct! Maybe more evidence of improvement in CoPilot, although the answer still needs tweaking.)

CoPilot is also great when I’m doing repetitive tasks such as describing the elements of an equation or diagram. Start describing the first element and it might give you the rest. And if you write a point followed by “Conversely, …”, CoPilot is often on the money.

Coding (efficiency gain: 10x)

Despite spending a lot of time in R, I am a crap coder. The simplest errors have me crawling Stack Overflow for hours. I struggle to build a structure when looking at a blank screen.

My typical approach now is to write a comment, let CoPilot do the first cut and then tweak the code until it is in shape.

That tweaking isn’t manual tweaking either.

If there is an error or problem that I can’t resolve, I’ll simply write:

The above code generates the error “PASTE ERROR”. I fix it by …

And a solution appears. Sometimes I’ll also paste the code and the error into ChatGPT and ask for code that does not have that error.

If the code looks overly complicated, a request to simplify often yields good results. (I’ve been asking ChatGPT to review some of my old code recently. I’m a bit embarrassed at how much more efficiently I could have written it.)

Here are two recent coding applications that I was particularly excited about.

Creating diagrams

In my lecture notes, I use ggplot to produce nice-looking graphs. (I’m slowly replacing old PowerPoint diagrams that still litter the notes).

Recently I wanted to generate a chart showing a probability weighting function from prospect theory.

I created an R code block and typed a comment:

#Plot of probability weighting function using ggplot2

Here’s the result with the diagram rendered below:

Exactly what I wanted. When I implemented this in the notes, all I did was tweaked the style and added a 45-degree line.

CoPilot’s offering uses Prelec’s (1998) probability weighting function. Whether it picked that up from earlier text or just gave the most common function for probability weighting, I don’t know, but it’s what I would have used if doing it manually.

CoPilot didn’t offer this full chunk of code at once. Each comment was offered, then the piece of code after it, one after the other. But the only work I did was writing the first comment and pressing tab several times as each succeeding comment or chunk of code was suggested. (CoPilot has certainly increased the level of comments in my code too.)

One thing I have noted is that CoPilot uses all of the text in the document in giving it’s suggestions. In writing this post I wasn’t able to replicate what I did when writing the lecture notes. I got better results in the lecture notes themselves. A few paragraphs about probability weighting before I ask for the code generates much better results than asking for the chart straight up.

Converting code across languages

My second example relates to a proposed reproduction of the results in Berkeley Dietvorst’s Algorithm aversion: People erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. Data and the code for analysis was available on ResearchBox.

The problem was that the code was in Stata, I don’t have Stata, and I have no desire to learn Stata. So, I pasted the code into ChatGPT and asked for a conversion to R. What I received was 90% of the way there. Initially there was an error, but ChatGPT solved the error first shot. I then had to tweak a couple of the variable manipulations and specify that some of the t-tests were paired t-tests, and that was it. In less than 10 minutes I had code that was reproducing exactly the results from Study 1.

Generating quiz questions (efficiency gain: 3x)

One of the best ways to learn is to be tested. As a result, I offer students in my undergraduate subject a series of practice quizzes that they can work through. In the first class I tell the students about the effectiveness of spaced repetition as a learning technique. They can then use the practice quiz questions on an intermittent basis to test whether they have learnt core concepts. (When I find the bandwidth, I plan to implement those quiz questions in Orbit or something similar, and place them through the online notes.)

Some questions are easy to generate: definitions and the like. But it’s hard work to generate questions in bulk and I struggle to generate plausible-sounding but incorrect answers to multiple-choice questions.

I now ask ChatGPT to generate them. In the prompts, I vary in the specificity of the questions. “Give me 20 multiple choice questions testing the concept of loss aversion.” “Give me 20 multiple choice questions testing prospect theory.” And so on. Out of each batch of 20, only a few will be suitable. There might be no correct answer or two correct answers, or ChatGPT might confuse concepts. But by tweaking my instruction by, say, describing the level of the students (undergraduate) or more explicitly defining the concept, it doesn’t take long to get 10 or so good questions.

I haven’t used ChatGPT to generate assessable quiz questions yet, but I’m planning to use it for the upcoming final exam. That exam is a closed-book AI-invigilated exam, so is less vulnerable to someone simply feeding the questions back to ChatGPT. One idea I’m tempted to try is to feed it some previous year’s exams and ask for new exams on the same concepts.

Writing organisational fluff (efficiency gain: 2x)

Work in any decent-sized modern organisation and you will have to write some level of fluff to satisfy the higher-ups, clients, government requirements and the like.

I am hopeless at those tasks. I have to invest heavily to make fluff sound decent.

My approach to these exercises depends on the degree of pointlessness.

If the task relates to a process that will have zero impact on what anyone will do, I simply give the task to ChatGPT, let it do the first cut and then tweak as required. One or two sentences of guidance often gets you 80% of the way there.

If I think there is a positive benefit to the task, or it’s for public consumption, I’ll be more proactive first up. I will write a rough draft first, not caring much about the writing but making sure the concepts I want to include are there. It might be in dot points. Then I’ll ask ChatGPT for a version that is “clearer”, “simpler” or “better written” or “for a ten-year-old”. I often find this process works best in two stages. The “clearer” version often uses the same words as me, but structures them better. Then I ask ChatGPT to write it again, but instructing it to “forget about the original text.” I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how good some of those second versions are.

Slide filler (efficiency gain 2x)

I’m not a big fan of pointless eye candy in slide decks. But if you’re doing pre-recorded material (see below) and you don’t want your mug on the screen, you sometimes need some filler. In that case, I head straight to DALL-E. I’ve adopted a theme for my lecture slides - black and white line drawings - so I ask for a black and white line drawing of something related to what I am talking about.

This is much quicker than hunting for images with open usage rights.

Compared to ChatGPT, DALL-E seems pretty lame. It still struggles with concepts such as “on” or “ten” or “without writing”. Sometimes I’ll give up on a more complex concept (a deck of cards on a table) and go for something simpler (a deck of cards). I’m looking forward to GPT-4 sitting behind an image generator.

I’ve also tried Stable Diffusion but found it was much harder work to get something I can use.

What’s next?

AI-voiced lectures

My next frontier is artificial voice generation for my pre-recorded lectures.

Last year - my first year taking the undergraduate behavioural economics subject - the subject was structured as two hours of live (but online) lectures and one hour of tutorials (either online or in-person). Both lectures and the online tutorial were recorded, so students could watch at another time. The net result was limited attendance - and most students didn’t watch the videos either.

This year I thought I’d move the subject out of the 1950s and make it a combination of some short pre-recorded videos, interactive online seminars and tutorials. This approach has backfired - the students don’t watch the videos and don’t want to interact - but that’s a story for another post, perhaps in combination with my review of Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education.

To produce the videos I’ve written scripts, which also form the subject notes. I read that accompanied by slides. I’m a hopeless off-the-cuff speaker, so for anything that’s going to be recorded and treated as a long-term asset, I’m scripting.

There are three pain points in this exercise. First, I speak too fast (even when I think I’m speaking slow) and I enunciate many words poorly. Second, recording takes a lot of time. I rarely get a two to five-minute video in a single take. Third, if I want to tweak the recording, I need to either re-record solid chunks of text or fiddle around with video edits.

So, why not get an artificial voice to do the speaking?

I’ve been experimenting with Murf.ai, Speechify, play.ht and Eleven. Eleven has comfortably the most realistic voices but doesn’t yet appear to have an easy way to create video using slides. If they introduce that, I’m fully on board. Murf.ai allows me to pair slides and text to create videos, but the voices still sound a bit robotic. But with the ability to pace their speech, Murf.ai is already a better option than me. And they’ll only get better.

The production process is then easy. Upload the text (although I do have to write out the equations in the course notes in text). Upload the slides and match to the text. Click play and the new video is generated.

With a setup such as this, if I want to tweak parts of the videos, I can simply edit the written text and generate a new version. Adding or editing slides is also simple as they are uploaded and matched to the new text. I’m also able to run much sharper slide changes as I can time exactly the transitions.

An interesting question about the artificial voice-over is how the university (and students) will take it. Do they see it as a lazy option? (When I taught at the University of Sydney in 2020 during the early stages of the pandemic, you weren’t allowed to use pre-recorded videos from one semester in a later semester. Someone hated the idea that the academics might not be working hard enough …) If I were able to clone my voice, this could become a mute issue. play.ht and Eleven have the ability to “clone” your voice, but neither can handle non-American accents. The rhythm of my cloned voice (maybe my natural rhythm) also seemed a bit clunky.

I think the artificial voice-over is a great option. Academics should be investing in developing high-quality assets that can be re-used rather than bumbling along with low-quality off-the-cuff lectures. They can then invest their time in the other parts of teaching: the in-person seminars and tutorials where students can get the personalised bit of their education.

This approach does point to a challenge for higher education providers. Once you’ve got high-quality recorded material for basic courses, why would you want them generated by each lecturer in each university? Someone could produce an amazing Behavioural Economics 101 (I want the Dave Malan CS50 version of this), other lecturers can subscribe to the service and they can now focus on those human bits (not that most students want that…).

I’ve also started looking at options to create an AI avatar - either based on videos/photos of me or a random AI avatar - for some parts of the videos. I’m leaving that one for the moment but can see myself revisiting in the next year.

Chat integrated with CoPilot (and other Microsoft tools)

At the moment I have multiple streams of access to these tools. I’m looking forward to chat appearing in Copilot - I’m on the waiting list to access - which will remove the need for the separate browser with ChatGPT.

GPT-4 is also coming to other Microsoft tools soon. If I don’t have to exit PowerPoint to get my images, that’s an extra efficiency.

I’m largely in the Mac ecosystem, but Apple seems absolutely crap in the world of assistants/chat. (“Hey Siri, tell me this most basic fact about the world.” “I’ve sent some irrelevant web results to your iPhone…..”) If at some point these tools become tied to Microsoft hardware or Windows, I’m moving.

(I exited the Google ecosystem when I had trouble sharing a file from Google Drive because it breached the terms of service. It was a document that included the words “vaccination” and “scepticism”, although if you see the resulting post, you can see the Google algorithm was pretty crude. At that point I opted for what I hope is a bit more privacy and jettisoned Google…)

Getting going with Github Copilot

The below gives the basic steps to achieve my setup.

If you are an academic, you can sign up for (free) academic access to CoPilot at this link. If you’re not an academic or student, sign up for $10 a month as described here. You’ll need a Github account to do this. I think the $10 a month is worth it, but the free ChatGPT will give you most of these gains with a bit more work.

Visual Studio Code is available here. (I use the Mac version.) Download and install.

Install the Github CoPilot extension into Visual Studio Code (or the Github CoPilot Nightly extension if you want access to features earlier). Instructions on installing the extension are here. On installation you’ll be prompted to login to GitHub to gain access to authorise CoPilot.

Once you have done that, using CoPilot is easy. You simply type. As you type, you will be given suggestions.

I write in markdown (or as noted above, a flavour of markdown called Quarto). It allows me to include \LaTeX math and R computations within any document (as I have in this post). If you’re an academic stuck in the \LaTeX ecosystem, you can also write in Visual Studio Code wholly in \LaTeX. (Although I say jettison that dinosaur and use \LaTeX math in a markdown document - that ability to add computations is worth it, and the readability and experience so much easier.) You can also just wait until GPT-4 appears in Word. I expect that’s not too far away.